- Type of Hakhshara

- vocational retraining, ICA preparation, Youth Aliyah preparation, Middle Hakhshara (Mi-Ha), regular Hakhshara, Religious Hakhshara

- Founded

- 1932

- Opened

- July 15, 1932

- Closed

- September 1943

- Operating Area

-

230 hectareCa. 230 hectares as well as additional useable land such as meadows, pastures, paddocks and woodland.

- Areas of Training Offered

-

horticulture, home economics, agriculture, animal husbandryLivestock farming (cattle, horses, pigs), poultry farming (geese, turkeys, ducks, chicken), gardening (fruits and vegetables), arable farming (grains), workshop (locksmithing, cartmaking, blacksmithing, carpentry), dairy production

- Description

-

On the initiative of the central office for Jewish Migrant Welfare Association (Jüdische Wanderfürsorge) and after several years of preparations, the Landwerk Neuendorf on the Neuendorf estate in Brandenburg (near Fürstenwalde) started operating in 1932. It was originally planned to be a Jewish workers’ colony to provide training and employment opportunities for Jewish unemployed and migrant workers during the Great Depression. The center was financed by the Jewish Workers’ Aid Association (Jüdische Arbeitshilfe e. V.) Landwerk Neuendorf in Berlin, which had been able to take over the estate from the heirs of the former Jewish owner, Hermann Müller, with the support of the Prussian Ministry of Welfare, the Prussian State Association of Jewish Communities and other Jewish charitable organizations.

Due to the dramatically changed conditions following the handing over of power to the Nazis in 1933, the Landwerk was hardly able to function in its intended purpose. Instead, the focus was on agricultural and home economics training as a prerequisite for emigration. One exception was initially the so-called Voluntary Work Service (Freiwillige Arbeitsdienst (FAD)), active throughout the German Reich and which Jewish institutions such as the Landwerk also took part in. In Neuendorf, Jewish young unemployed people as well as secondary school students who were kicked out of school were therefore able to find temporary employment, in particular in the reclamation of fallow land. In 1933/34, a group from the Federation of German-Jewish Youth (Bund deutsch-jüdischer Jugend (BdjJ)) also worked in the Landwerk. Their training took place within the framework of the so-called Jewish vocational retraining, which at the time still aimed to create a “German-Jewish synthesis” and opportunities for Jews to support themselves in agricultural or working trades.

In the 1930s, the Landwerk Neuendorf was by far the largest Jewish farm training estate in Germany in terms of area. It offered numerous opportunities for agricultural, horticultural and home economics training for Jewish girls and boys to prepare them for Aliyah and their future communal life outside of Germany. The manual skills and trades needed for farming could also be learnt there.

The size and variety of farmland and livestock allowed for practical training, usually lasting two years. The estate had grain fields, woodland, extensive pastures, garden beds with vegetable crops, a park, a large greenhouse, numerous fruit trees and orchards and an apiary. The livestock included 140 cattle, 20–30 horses and, for economic reasons, around 350–400 pigs. There was also a poultry farm with geese, turkeys, ducks and a henhouse with 500 Leghorn chickens.

In the first years after the Landwerk was founded, further farmland was developed and the more labor-intensive horticulture was greatly expanded, which in turn increased the training capacities. There was also a workshop for all the work related to farming such as locksmithing, cartmaking, blacksmithing and carpentry, also used for training.

The home economics department, led by Erna Moch, included housekeeping, kitchen and laundry, and at times had to provide for a staff of 100 people or more. Training in home economics, which in keeping with the relatively strict division of gender roles was the domain of the girls, also included poultry and dairy farming.

The Landwerk was easy to reach thanks to the connection to the Oderbruchbahn train line with two stations near or even on the farmland (the stop Waldfrieden and the station Neuendorf-Buchholz), which in turn helped to sell the goods produced at the farm.

Characteristic of Neuendorf were the different “training programs” supported by various Jewish organizations that took place alongside the Hakhshara in the narrower sense. Members of the Federation of German-Jewish Youth, groups of the Zionist organizations Maccabi Hazair, Habonim, the orthodox youth group Noar Agudati Israel along with halutzim supported by HeHalutz lived, trained and worked on the estate. At the same time, Youth Aliyah groups were preparing for their joint Aliyah and emigrants were being trained to settle in Argentina, Brazil and Australia. By 1936, around 600 people had emigrated in this way.

During the November Pogroms of 1938, the Neuendorf estate was also attacked. Alex Moch, the manager of the estate, and the trainees who were already adults were deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Oranienburg. Subsequently, Alex Moch was able to free his trainees from the concentration camp and emigrate together with them to England. The younger trainees had remained on the Neuendorf estate. The threatened closure and expropriation of the farm did not happen, but the running of the farm became increasingly coercive. Now some subject to the so-called “assigned labor” which had been forced on the Jews arrived on the estate.

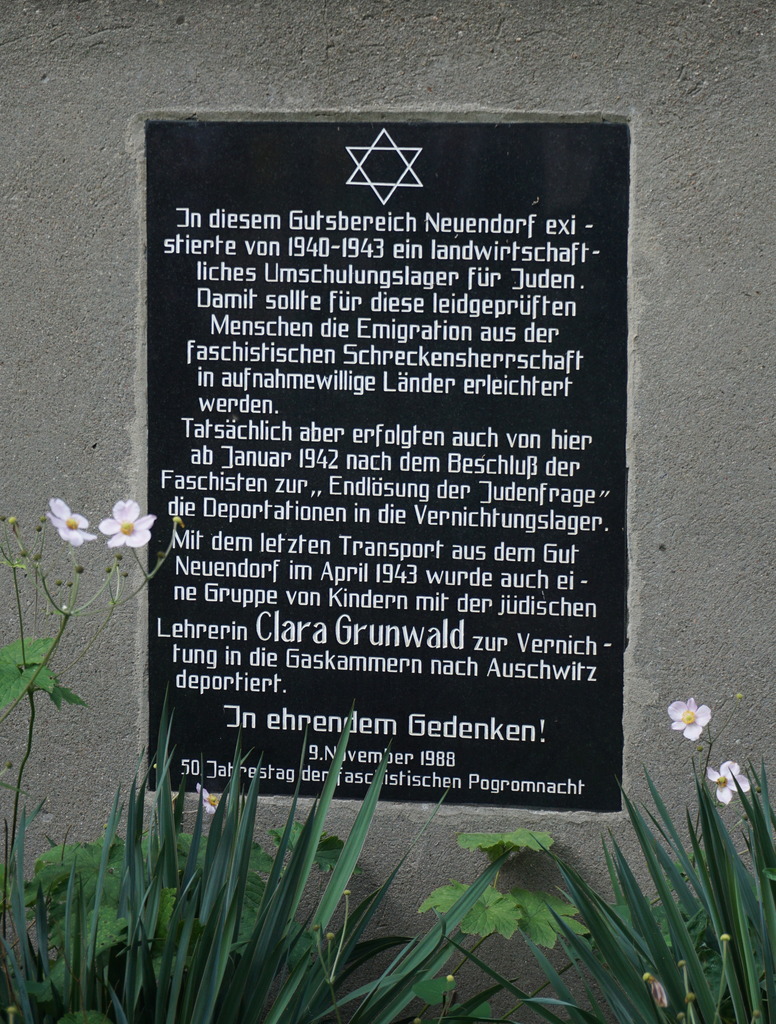

Landwerk Neuendorf became a forced labor camp for those remaining; other young people from other Hakhshara sites that had been forcibly closed down also came to Neuendorf. In June 1941, Martin Gerson, the manager of the Winkel estate, arrived with his family and all of the halutzim from there and took over the management of the farm. From 1942, Neuendorf was also used as a collection camp for deportations to Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. In June 1943, practically the last remaining Jewish inhabitants of the Landwerk Neuendorf were deported to Theresienstadt, including Martin Gerson and his family as well as some other teenagers. Most of those deported did not survive. Until the fall of 1943, a few halutzim (who had been classified as Jewish “mischlings” or “mixed-blood” according to the Nazi racial laws) carried out forced labor in Neuendorf. Afterwards, the estate remained a forced labor camp and also served as a logistical center for the surrounding forced labor camps.

Well over a thousand Jews were able to make Aliyah or emigrate thanks to their training at the Landwerk Neuendorf estate.

In 1950, the Neuendorf farm became a state-owned estate (Volkseigenes Gut (VEG)) of the GDR. The buildings and land are partially preserved and serve as living and working quarters. Thanks to the work of the association “Geschichte hat Zukunft – Neuendorf im Sande e.V.” (https://geschichte-hat-zukunft.org/)”, cultural events, exhibits and memorials impart the historical significance of the former Jewish training center.

© CC-BY-SA-4.0

© CC-BY-SA-4.0

© CC-BY-SA-4.0

- State of Conservation

- partially preserved

- Related Organizations

-

Bund deutsch-jüdischer Jugend (associated)Habonim Noar Chaluzi (Deutschland) (associated)Hechaluz. Deutscher Landesverband (associated)Hilfsverein der Juden in Deutschland (associated)Jewish Colonisation Association (associated)Jüdische Arbeitshilfe e. V. (Landwerk Neuendorf) (sponsorship)Jüdischer Pfadfinderbund Makkabi Hazair (associated)Noar Agudati Israel (associated)

- Related Persons

-

Gerson, Martin (director)Moch, Alexander (director)Moch, Erna (director)

- Literature

-

Anneliese-Ora Aloni-Borinski: Erinnerungen 1940–1943. Nördlingen: Verlag G. Wagner 1970.

Clara Grunwald: „Und doch gefällt mir das Leben“. Die Briefe der Clara Grunwald 1941–1943. Mannheim: Persona-Verlag Buchholz 1985.

Landwerk Neuendorf, in: Zeitschrift für Jüdische Wohlfahrtspflege und Sozialpolitik 4 (1932). pp. 257–260.

Harald Lordick: Das Landwerk Neuendorf. Berufsumschichtung – Hachschara – Zwangsarbeit, in: Ulrike Pilarczyk; Arne Homann; Ofer Ashkenazi (eds.), Hachschara und Jugend-Alija. Wege jüdischer Jugend nach Palästina 1918–1941, Steinhorster Beiträge zur Geschichte von Schule, Kindheit und Jugend. Gifhorn: Gemeinnützige Bildungs- und Kultur GmbH des Landkreises Gifhorn 2020. pp. 135–163. online: <https://doi.org/10.24355/dbbs.084-202104201055-0>

Harald Lordick: Das Landwerk Neuendorf in den Novemberpogromen 1938, in: Arbeitskreis Jüdische Wohlfahrt (11/08/2020). online: <https://akjw.hypotheses.org/1032>

Harald Lordick: Hachschara und ‚Berufsumschichtung‘ in der Mitte der 1930er Jahre – Das jüdische Landwerk Neuendorf im Spiegel zeitgenössischer Erfahrungsberichte, in: Arbeitskreis Jüdische Wohlfahrt (06/07/2020). online: <https://akjw.hypotheses.org/779>

Harald Lordick: Landwerk Neuendorf in Brandenburg. Jüdische Ausbildungsstätte, Hachschara-Camp, NS-Zwangslager – Gedenkort?, in: Kalonymos 20. Jahrgang (Heft 2) (2017). pp. 7–12. online: <http://www.steinheim-institut.de/edocs/kalonymos/kalonymos_2017_2.pdf#page=7>

Rudolf Melitz (ed.): Das ist unser Weg - Junge Juden schildern Umschichtung und Hachscharah. Berlin: Joachim Goldstein Verlag 1937. online: <http://d-nb.info/1032728663>

Recommended Citation

Harald Lordick, Landwerk Neuendorf, in: Hakhshara as a Place of Remembrance, November 18, 2024 (as of December 15, 2023). <https://hachschara.juedische-geschichte-online.net/en/site/1> [February 19, 2026].

Address

Gutshof 115518 Steinhöfel